The Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station operated from 1874 until a mass decommissioning in 1954. 2024 marks 150 years since the inception of the United States Life-Saving Service on the Outer Banks. The Chicamacomico station is planning a celebration in October to commemorate the men who bravely served at this location.

Article and photos by Summer Stevens, republished with permission from The Coastland Times.

[email protected]

Americans rightly remember and honor the men and women who have faithfully served in our branches of military to protect our country and its citizens. But it’s time to add to our remembrances the remarkable courage of the United States Life-Saving Service surfmen who braved turbulent and often icy waters to rescue vessels and sailors in peril.

From 1874 to 1954, servicemen throughout the United States were dispatched in an effort to rescue roughly 178,000 people.

And they were successful in rescuing a staggering 177,000 of them.

An estimated 450 Life-Saving Stations were built throughout the United States. Though mostly concentrated along the Atlantic, some were built along the Great Lakes, the Gulf, and the Pacific. United States Life-Saving Service (USLSS) was absorbed into the US Coast Guard In 1915.

2024 marks 150 years since the United States Life-Saving Service (USLSS) was established on the Outer Banks.

The Chicamacomico station was the first United States Life-Saving Station to be commissioned. The 1874 station has been moved several times but now rests just a little farther inland of its original location.

The Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station was the first to be commissioned on December 4, 1874, followed quickly by six other stations along the Outer Banks coast at Jones Hill (Currituck Beach), Caffeys Inlet, Kitty Hawk, Nags Head, Bodie Island (Oregon Inlet), and Little Kinnakeet (Avon). Over the next three decades, another 22 stations would be built along the North Carolina shoreline, with the concentration from Currituck to Ocracoke.

Local people were initially hired to man the stations seasonally. After the tragic wreck of the Huron in 1877 and the Metropolis only two months later, resulting in the deaths of 183 men, the U.S. government kept the stations open year-round. When Sumner Kimball took over in 1878, he standardized the training, equipment and spacing of the stations. Kimball’s leadership in one critical area determined the success of the stations.

Rather than having political appointees lead the stations, he sent superintendents to the local communities to meet the people, said Larry Grubbs, Chicamacomico Historical Association president. “They asked themselves, ‘Who’s the most upstanding, brave, conscientious, good decision maker? Who will all the other men follow?’”

A second life-saving station was built in 1911 and now houses the museum store and two floors of life-saving photos and artifacts.

The very first one completed is, interestingly, also the best preserved in the country. The station in Chicamacomico, in what is now called Rodanthe, has all of its original buildings (except for the cookhouse which burned down and was rebuilt) and is open to the public for self-guided tours.

Remarkably, many people don’t even know it exists.

“All these visitors drive from Nags Head and Duck and drive right past here twice. People just don’t know about it,” said Grubbs. “I’m not knocking anything else … but all these visitors drive to the lighthouse, to the Graveyard of the Atlantic, all these places, and drive right past us. I don’t think they realize that they’re driving by the most complete US Life-Saving Service site in the country.”

The Chicamacomico Station features the original 1874 life-saving station, which has been moved several times but now rests close to its first location; the 1911 life-saving station which now houses the Museum Store and Keeper’s office; two cookhouses; and a small boathouse. The station also houses the original Surfboat No. 1046. Some restoration work is taking place this year to reinforce and protect the original 1874 station.

The “Breeches Buoy” was used in rescue operations. A re-enactment using the same ingenious rescue equipment is performed weekly throughout the summer at the Chicamacomico Station in Rodanthe.

To preserve the stories of the men who served in Chicamacomico, every Thursday at 2 p.m. from Memorial Day to Labor Day, a team of volunteers reenacts a historic shipwreck rescue at the Chicamacomico Station. During the Beach Apparatus Drill, volunteers explain the gear that was used by the surfmen and even demonstrate a rescue with an audience member on land.

They do this because the acts of bravery are worth remembering and they are worth telling.

In the 1874 station, original wood steps lead up to the men’s bunk area and to the lookout. Every step is worn thin in the middle. That’s from the thousands upon thousands of feet — faithful feet, weary perhaps — that have climbed back and forth, in service to unknown men and women aboard vessels in distress.

The original Surfboat No. 1046, which was used in the 1918 Mirlo rescue, is preserved at the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station in Rodanthe.

At Chicamacomico, rescued sailors would take shelter in the bunkroom if necessary. Rumor has it there used to be blood stains on the floor that went back to the Mirlo rescue in 1918. The Mirlo rescue was the most decorated rescue in the history of the US Life-Saving Service. A six-man Chicamacomico crew led by Captain John Allen Midgett rescued 42 men aboard a British oil tanker that had been torpedoed by a German U-boat. Nine other men perished before the rescue crew arrived.

The men made four attempts to pass 18- to 20-foot breakers in Surfboat No. 1046 to motor out to sea. When they arrived, exploding gasoline barrels were shooting sheets of fire 100 feet into the air. The surface of the water was on fire. Six men clung to an overturned lifeboat, and survived only by staying underwater as long as their breath would hold, then returning to the surface for a swift lungful of air before submerging again.

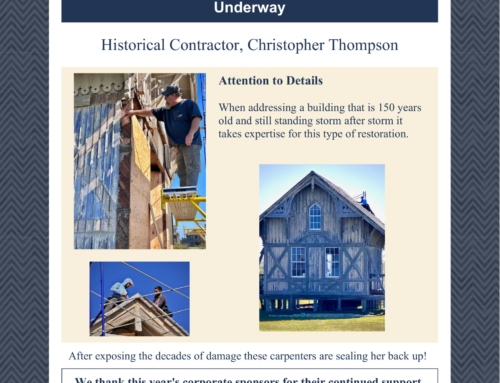

Chicamacomico Historical Association president Larry Grubbs and the association’s board of directors have commissioned a restoration project on the east side of the 1874 life-saving station.

For four hours the rescue crew worked to bring 42 men to safety, making four trips through the perilous breakers to reach the shore.

Notes from Mirlo Captain William Roose Williams said that Captain John Allen Midgett and his crew had “done one of the bravest deeds which I have ever seen by entering into the fdires as they apparently did, as it would have bveewn impossible for me only having oars and the exhausted state of the boat’s crew to have done the same” [sic].

This is just one of hundreds of rescue stories. It is a history that should not be swept away.

A hundred years after the inception of the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station on the Outer Banks, the Chicamacomico Historical Association was founded with a mission to preserve the historic site and tell its unique story.

The non-profit organization owns and operates the museum site and raises its own funds. All monies from admission fees, memberships, donations and museum store purchases go toward the preservation, restoration and operation of the Chicamacomico site.

For the 150th anniversary, the organization is planning a big celebration October 11-13 and a #LegacyofLifeSaving activities throughout the year.